Explore stories from families living with Lesch-Nyhan (HND), the variant form. Learn how each journey sheds light on different forms of the condition and strengthens our shared understanding, connection, and hope.

Lesch-Nyhan Variant (HND)

Lesch-Nyhan can appear in different forms, each affecting individuals in unique ways. This section shares real stories from families and individuals living with a loved one living with a Lesch-Nyhan variant (HND)— their experiences, challenges, and insights. By learning from each story, we deepen our understanding of the condition’s spectrum and build a stronger, more connected community grounded in hope and shared knowledge.

-

Earl’s Story: A Life of Strength and Determination

For most of his life, Earl Husak ”Butch” didn’t know that the challenges he faced had a name. As a young boy, he was told he had cerebral palsy. He grew up accepting that diagnosis and learning to adapt. “There was no difference,” Earl says. “I never knew what a normal person had. I never knew the difference.”

But there were early signs that something more was going on. “I think I was four years old,” he recalls. “Me and my mom and dad were up at Grandma’s house. I was using the potty chair, and there was blood in the can. My Grandma said, ‘You’ve got to take Butch to the doctor—that ain’t right.’ They never did nothing more about that. But I remember that positively. I don’t know why I remember that, but I do.”

When his family moved to northeast Minneapolis, Earl started school like any other kid. “I used to walk to school every day—walked there in the morning, came home for lunch, and went back again. Sometimes I’d stop at Blacky’s Bakery they had some rolls,” he says with a grin.

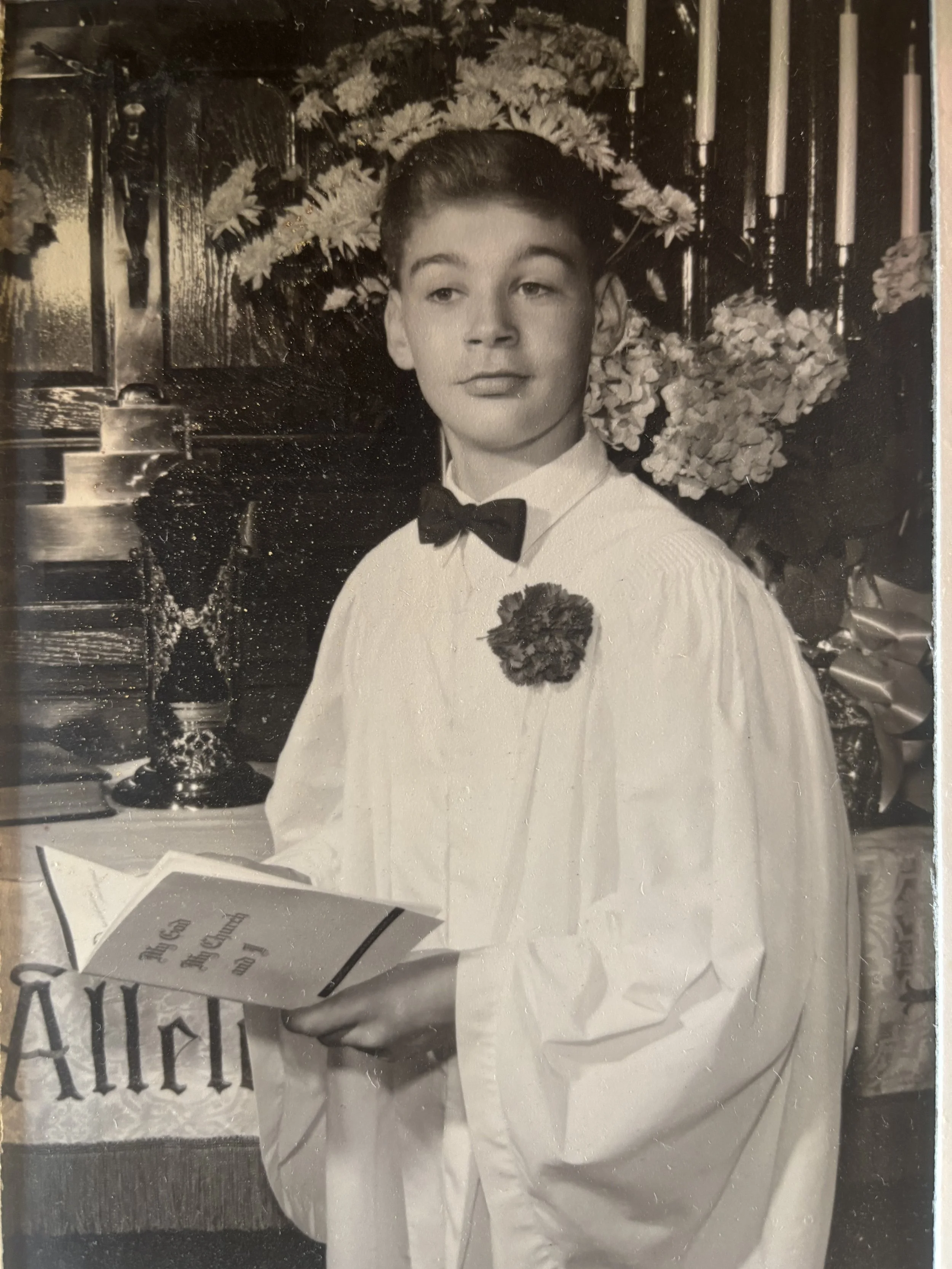

As he got older, health issues became harder to ignore. Just before his confirmation, Earl’s legs swelled so badly he couldn’t walk. At Gillette Children’s Hospital, the doctor told him he had gout—but even then, few believed it. “I spent a month in the hospital,” Earl remembers. “They finally did some tests and said, ‘Yes, you have gout.’ That was the first time I ever heard that.”

Adjusting to that diagnosis meant changes in his life. “The doctor said I couldn’t have spaghetti, pizza, or steak anymore,” he says. “My mom always made me something special instead. My dad used to get mad—‘He gets all the specials, I don’t!’” He laughs at the memory. “I still have all my schoolwork from kindergarten to fifth grade—spelling and everything. My teacher was L.R. Cameron. Ask me why I remember that. -I don’t know.”

Later, while working at United Cerebral Palsy, Earl met people who made lasting impressions. He recalls renting a home on 24th and Portland with his friend Jerry. “The woman who owned it was Mrs. Poons—she had been my second-grade teacher. She recognized my name right away. I couldn’t believe it after all those years.”

Life brought new milestones, too. At 30 years old, Earl got married—marking the start of another important chapter. Together, he and his wife built a family and a home filled with love, humor, and resilience.

Over time, Earl’s condition revealed more clues, and eventually, at the age of 65, he learned he had a variant of Lesch-Nyhan disease. “At first, I didn’t feel a difference,” he says. “I just kept doing what I thought I had to do. I can do anything anybody else can do. I can do a lot more than a lot of people can do. I put my heart in it.”

That same determination shows in one of Earl’s proudest accomplishments—building his own car, a vintage Whippet. He pieced it together himself, bolt by bolt. “I had my Whippet jacket on one day, and a guy came up to me and asked, ‘Do you have a Whippet?’” Earl recalls, smiling. “I said, ‘Yeah, I bought it in pieces.’ I pulled out a picture from my pocket to show him. He said, ‘Oh, boy.’ That made me feel pretty good.”

The Whippet isn’t just a car—it’s a symbol of Earl’s independence, creativity, and pride in what he can achieve.Even when doctors doubted his diagnosis, Earl stood firm. “I tell the doctors what I’ve got, and they don’t believe me. What am I supposed to do?” he says. “I tell a lot of people what I’ve got, and they don’t know the difference.”

Through it all, family has been Earl’s biggest source of strength—his daughters Andrea, Cara, and Nicole, his son-in-laws, his neighbor Gene, and his sisters. “They’ve helped me a lot,” he says. “They’ve always been there.”

Earl has also contributed to research, hoping his experience will help others. He traveled to Johns Hopkins Hospital to meet with Dr. Hyder Jinnah, one of the world’s leading experts on Lesch-Nyhan. Currently he is participating in the Purine and Pyrimidine study at the NIH with Dr. Oleg “The doctors and researchers helped me,” Earl says. “Anything they can find about me that helps somebody else—I want them to do that. How my coordination is, they see me, then they see somebody else. Maybe they can help them from me.”

Dr. Jinnah even gave him a letter to carry in case of misunderstandings with the police. “Half the time, they think I’m drunk,” Earl explains. “Dr. Jinnah told me, if that happens, show them the letter. Tell them you’re not.”

When asked what he wants doctors and researchers to understand about living with a Lesch-Nyhan variant, Earl doesn’t hesitate:

“How hard I have worked to have what I got. I worked harder than a lot of people do.”

And for others just beginning their journey with Lesch-Nyhan, Earl’s advice is simple but powerful:

“Do the best you can. Do the very best you can do.”

Now, at 82 years old, Earl continues to live with determination and gratitude. Each year, he looks forward to celebrating his birthday on Christmas Eve—a fitting day for someone whose life has been a gift of perseverance, humor, and love.

November 2025